<p><a href="https://www.ehu.eus/es/web/graduak/grado-filologia/profesorado?p_redirect=fichaPDI&p_idp=5577">Gidor Bilbao</a>, lecturer in the <a href="https://www.ehu.eus/es/web/estudiosclasicos/home">Department of Classical Studies</a> of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) and researcher in the <a href="https://www.ehu.eus/es/web/mlv/home">Monumenta Linguae Vasconum</a>, group, has described and analysed new-found poems by Arnaut Oihenart: '<a href="https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/ASJU/article/view/24095">Kobla berriak</a>'. These poems have provided him with a considerable amount of information regarding Oihenart's way of publishing, and about the metres he used and the popular tradition of that time. With the resources available today, Bilbao is convinced that other works from that era will continue to appear. And he warns that there is still much work to be done.</p>

Gidor Bilbao describes and analyses 'Kobla berriak' by Arnaut Oihenart

- Research

First publication date: 11/05/2023

On the Master's course in Linguistics and Basque Studies classical texts are analysed and the classical literature of Oihenart used to receive little mention until now. The author is well known among the students of Basque Studies, but in particular with regard to his collections of proverbs. But Gidor Bilbao has always found Oihenart's poetry attractive and beautiful. That is why he thought that Oihenart should also be studied in class, and so he took a closer look at the author.

Since when have you been following Oihenart's trail?

In the 1980s, the members of the research team and myself had been following Oihenart for a long time, above all in collaboration with Joseba Lakarra. Convinced that there would have been unknown manuscripts by Oihenart, we set about searching for them, from library to library. We did not find anything. A couple of years ago, however, I started looking for printed works by Oihenart rather than manuscripts. So while exploring the union catalogue of the antiquarian libraries of France, I came across the catalogue of the library of Grenoble.

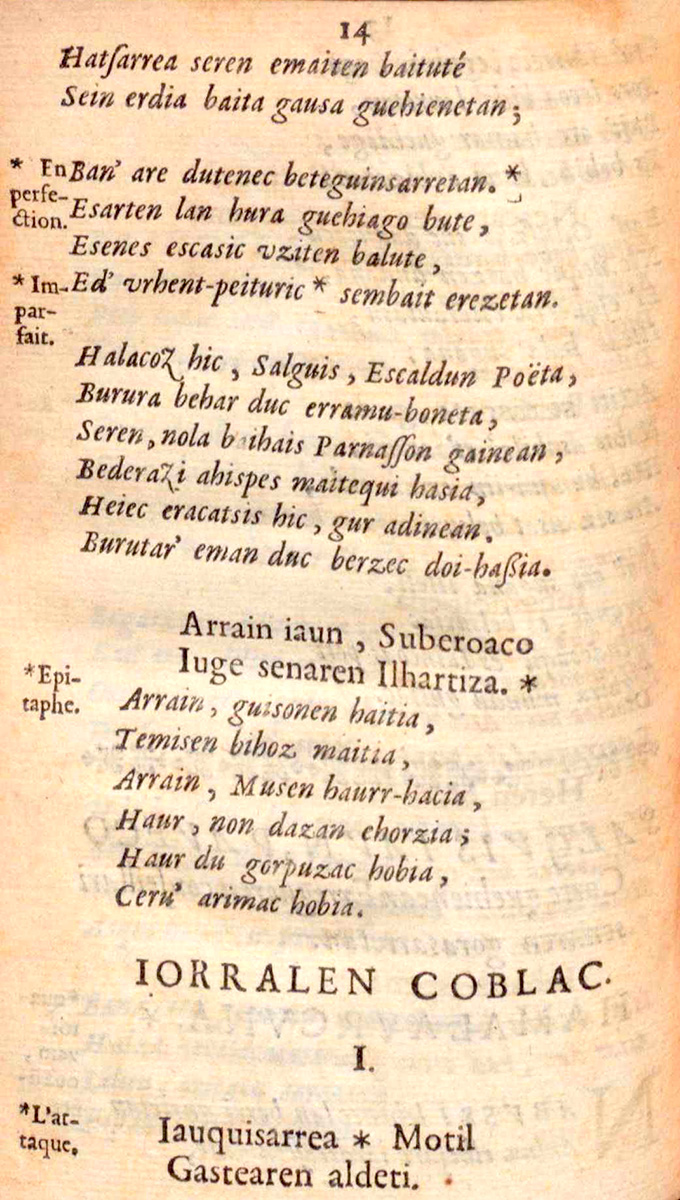

Bilbao acknowledges that he often has a tendency to be “capricious”. From time to time he accesses library catalogues that include antiquarian works to see if they have any new additions, as both library and archive catalogues and digitised photographs are evolving and improving day by day. Searches are also carried out by testing combinations of possible variants, spellings and errors in names and words. So when he came across 'Ot-en gastaroa neurtitzetan' he approached the library in Grenoble, because Ot was known to have stood for Oihenart himself. That is where Bilbao found a work entitled 'Cobla berriae' and realised that it comprised four more pages than the copy in the library in Bayonne.

|

|

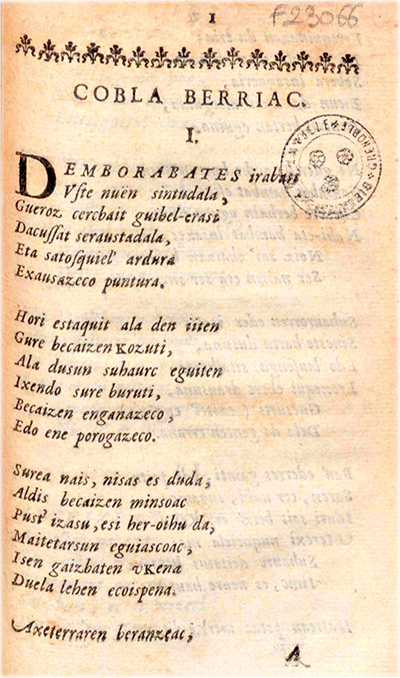

Image of the first page of the Grenoble copy. Photo: Gidor Bilbao |

What did you feel when you saw that you had an additional four pages to research Oihenart's work?

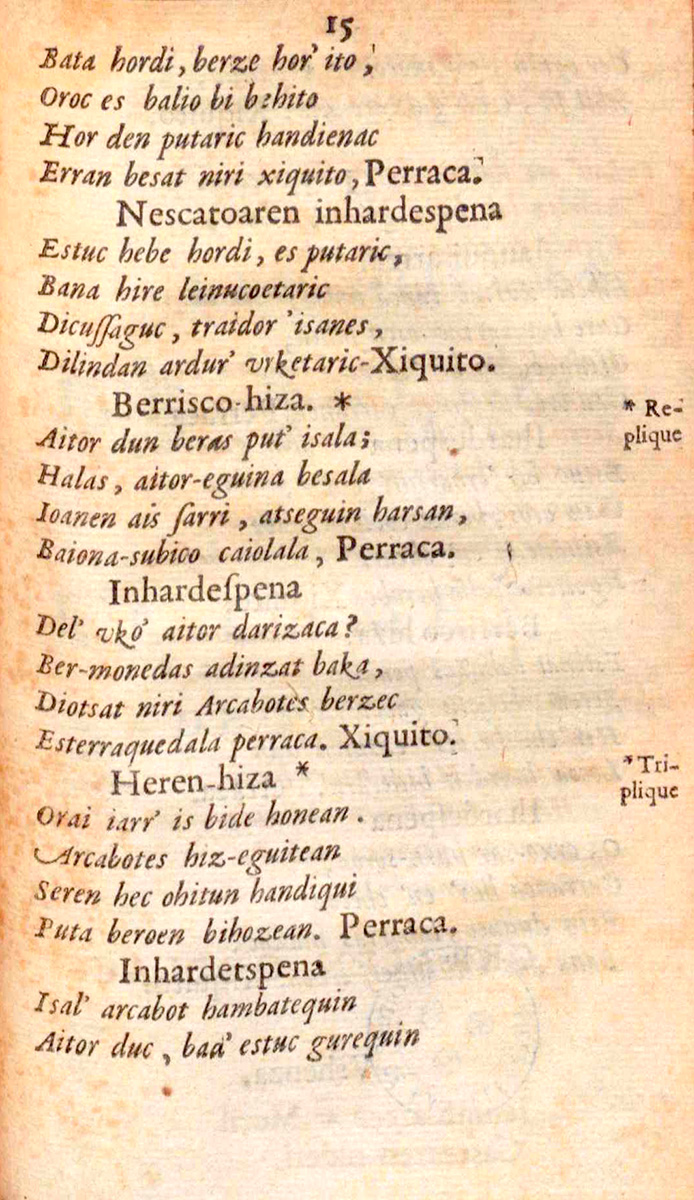

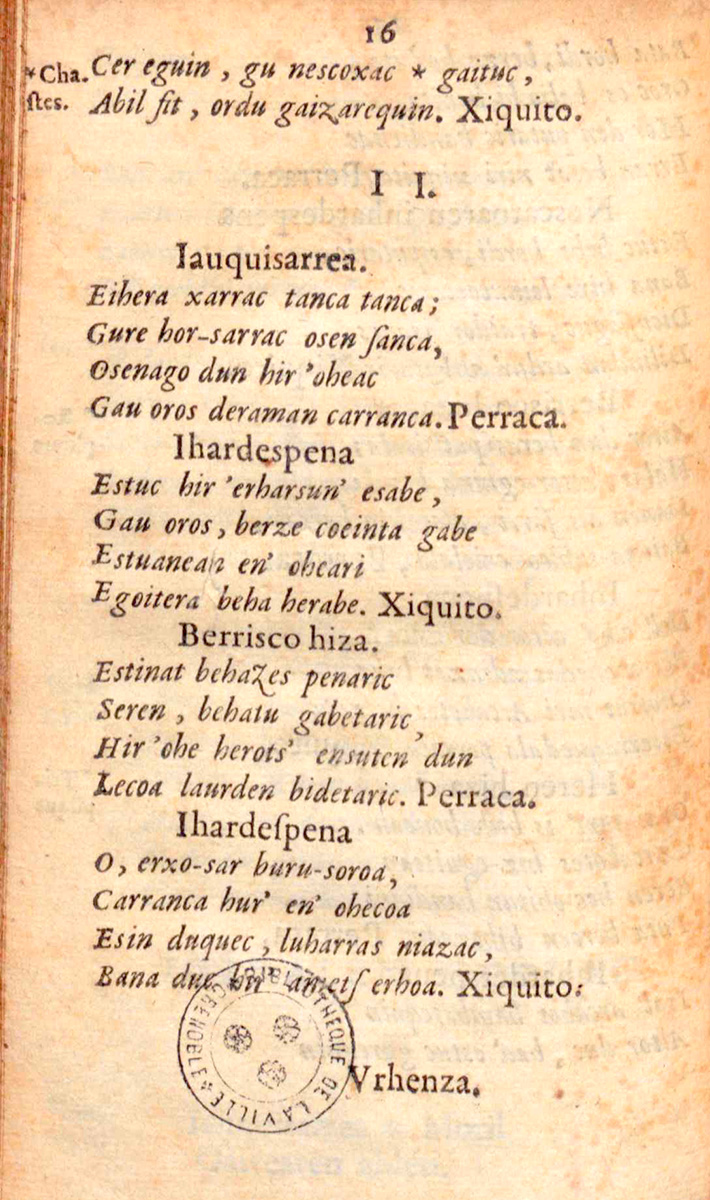

Joy, but at the same time questions arose. What were those poems? I immediately saw that one of the first pages contained one of Oihenart's classic love poems, as these have a poetry metre that has never been used. I think he wanted to show that poetry in Basque could use many kinds of metres. But the 'Jorraleen koplak' (The Slanderers' Verses) on the last pages made a significant contribution to literature, because they have taught us new things and, moreover, because, until now, we did not know that Oihenart had paid any attention to the folk tradition. Another important question also occurred to me. The title of the work appears on the first page, and is immediately followed by the poems. This booklet seemed to be a continuation of something else, but at the same time it is the first page. Why did Oihenart do that?

So he began to analyse what Oihenart did with other works taken to press. Bilbao then saw that nearly all of Oihenart’s works were collections of separate booklets, and he suspects that the author also acted in a similar way with his poems, in other words, he had produced a collection of poems that until now we know under the title 'Ot-en gaztaroa neurtitzetan'”, and then another collection, probably a continuation of it, called 'Kobla berriak'. Oihenart may have been planning to publish them all at the same time.

Gidor Bilbao is in no doubt that, in addition to studying the content of digitised works from a linguistic point of view, it is very important to analyse the works on paper, as paper also provides a great deal of information.

Why are you sure when you say that if you keep looking you will find more things?

In the 1980s and 1990s, we used to go to libraries asking if there were any works of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries not written in French or Latin. What is more, librarians often had a well-developed concept of private property, so firstly their consent had to be obtained in order for such works to be shown. So in addition to the technological aspect, there has been a huge change in the willingness of librarians and libraries when it comes to showing and making available to the general public the works they have in their catalogues. I think it is the job of teaching staff to show that a lot has been done but that there remains much to do. We now have resources that we didn't have before. But I have few doubts. New texts of the 16th and 17th centuries are not going to be found every day; but some of the 18th and 19th centuries will appear. Those of the 19th century have not yet been properly studied. There is certainly much work to be done.